What’s with the dodgeball references? I’m out of the loop apparently.

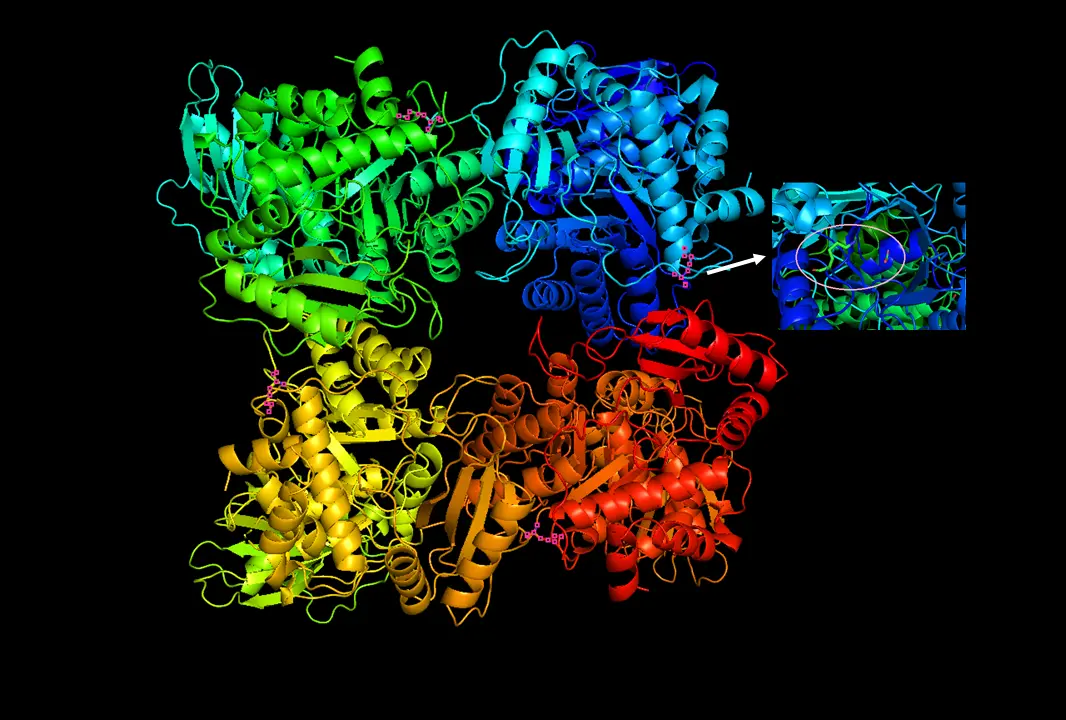

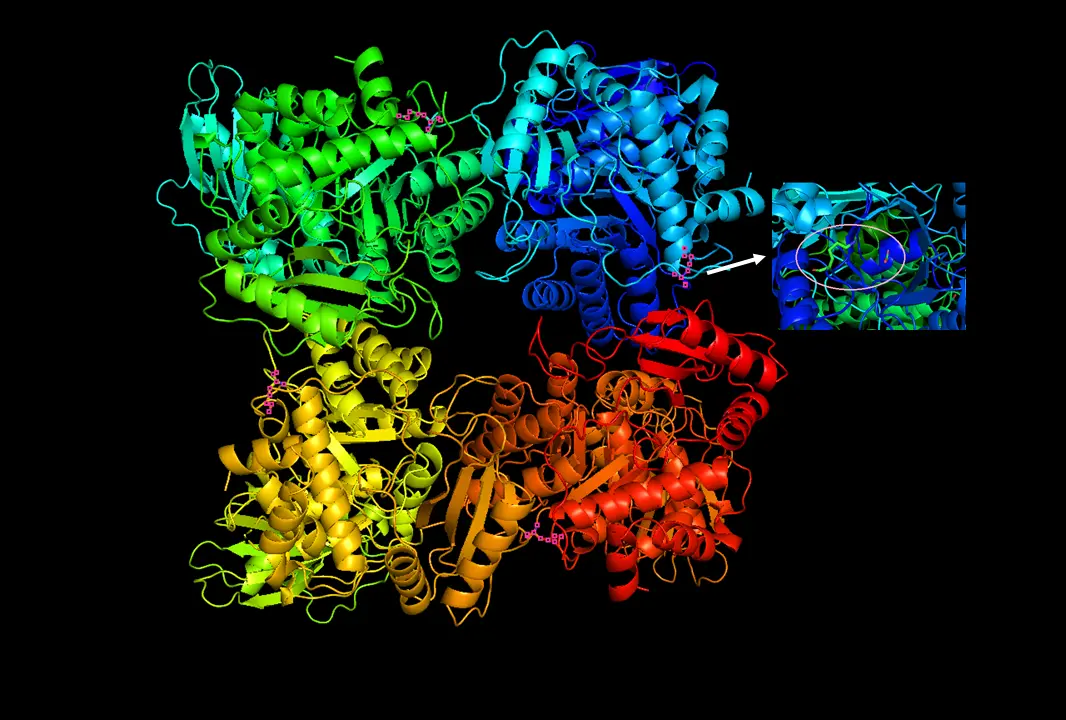

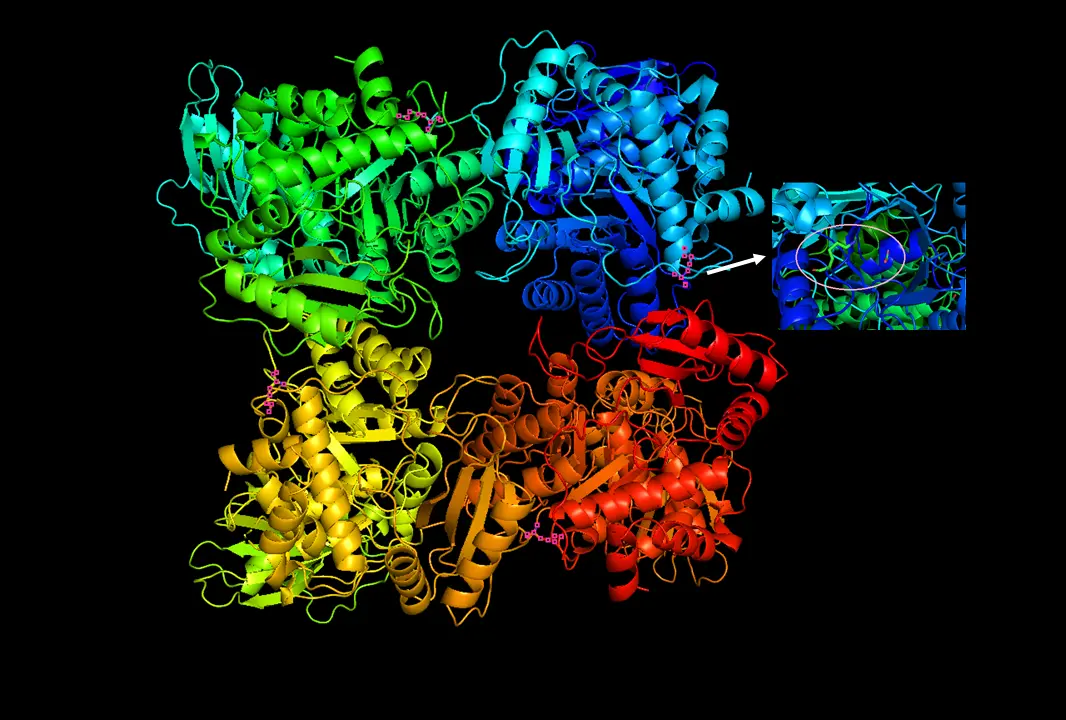

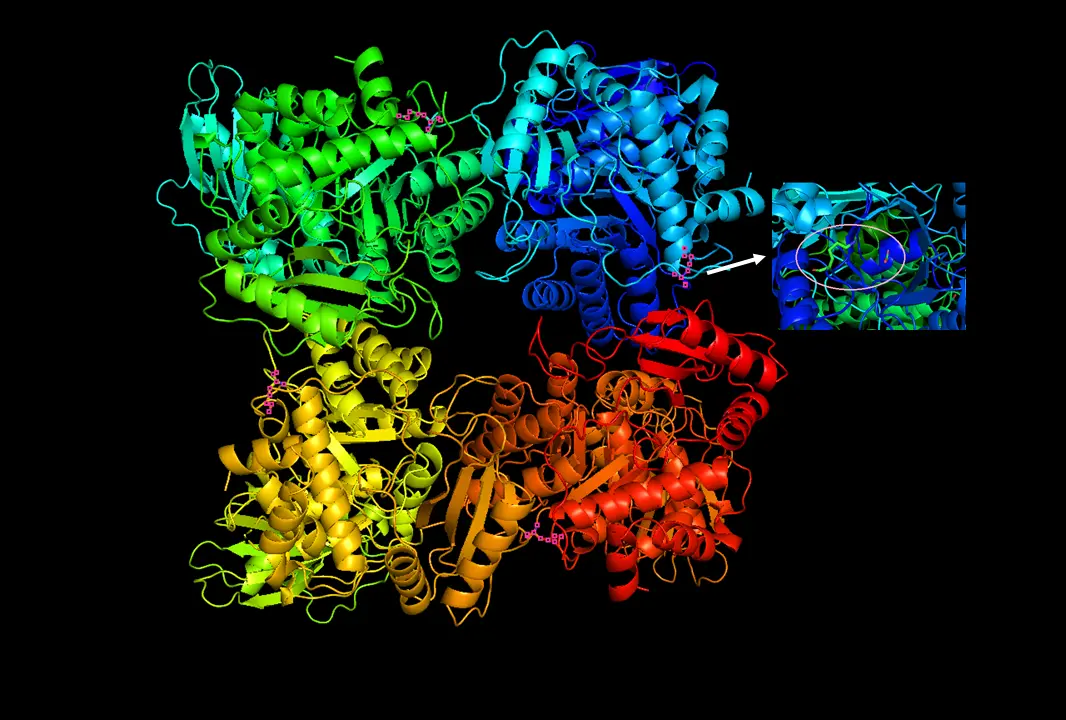

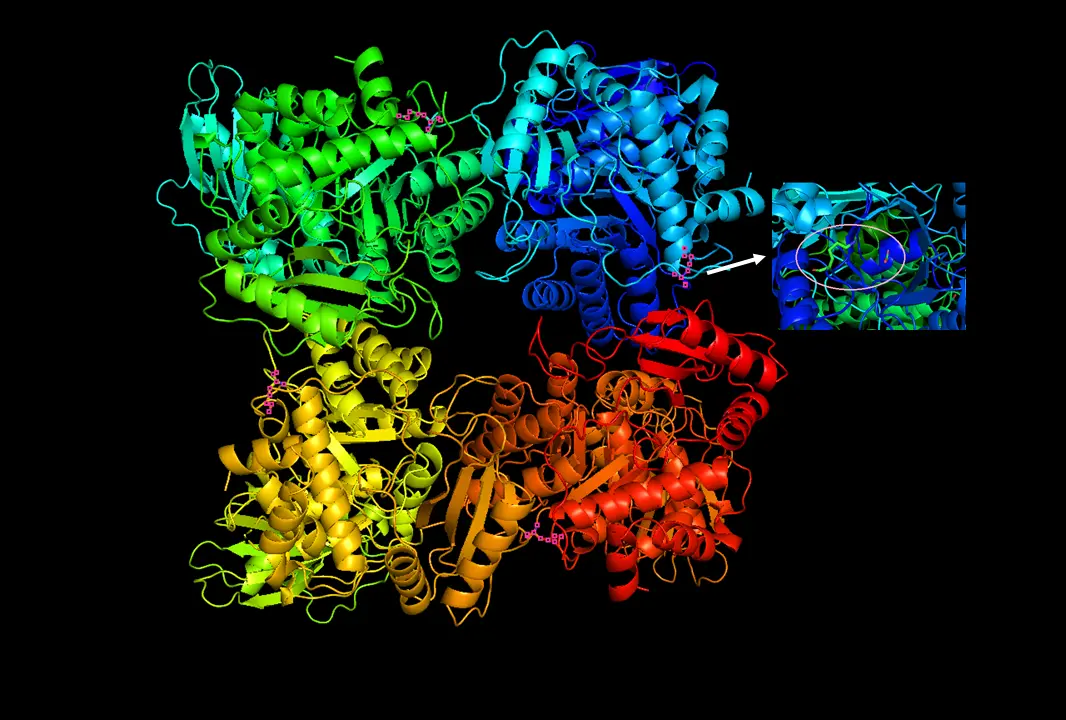

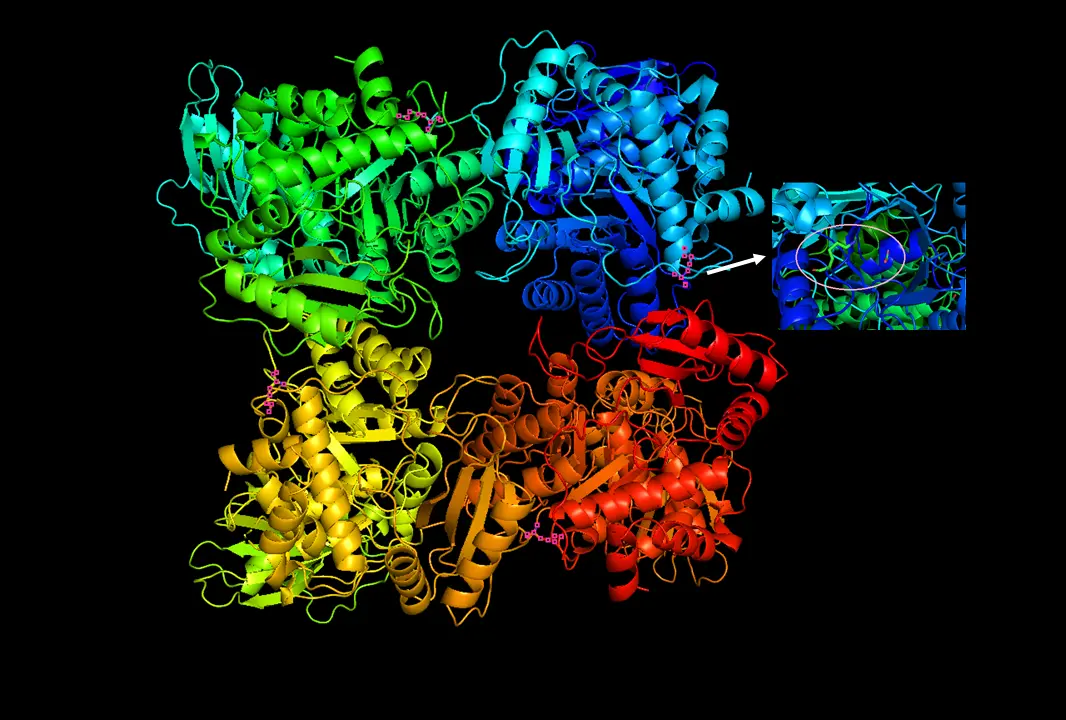

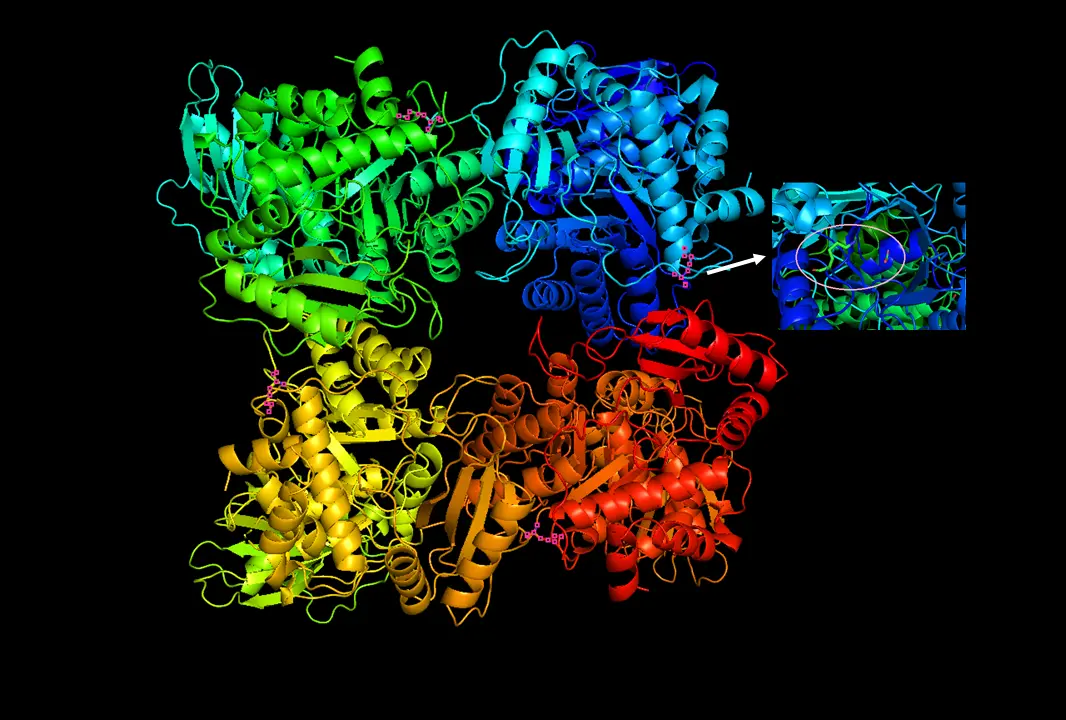

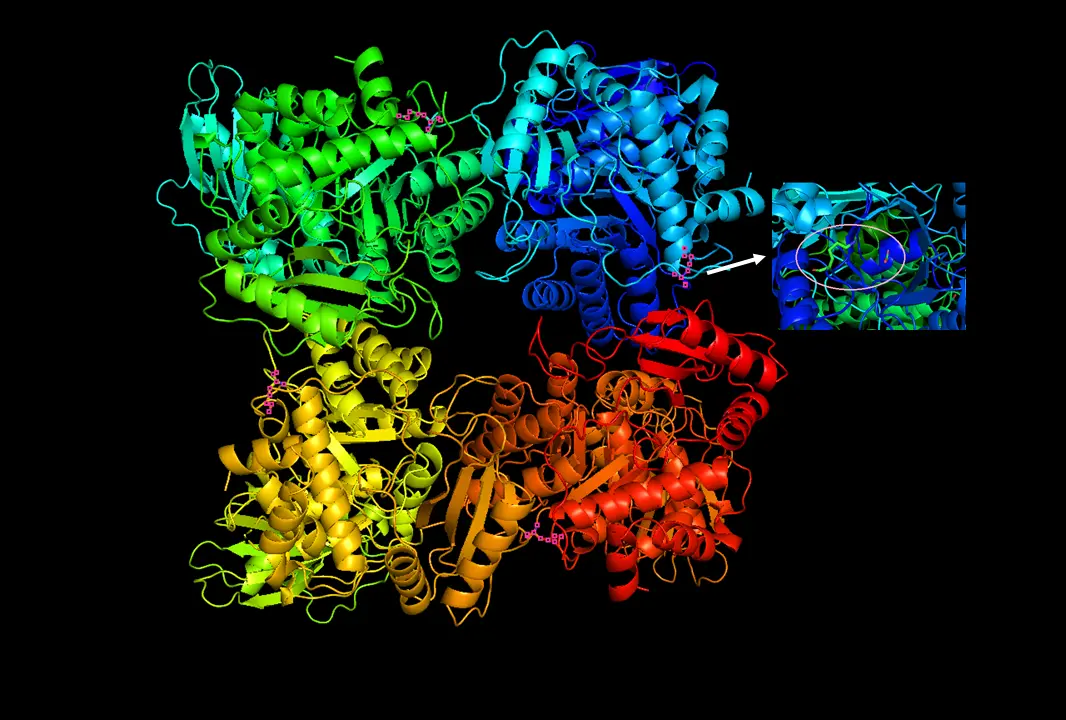

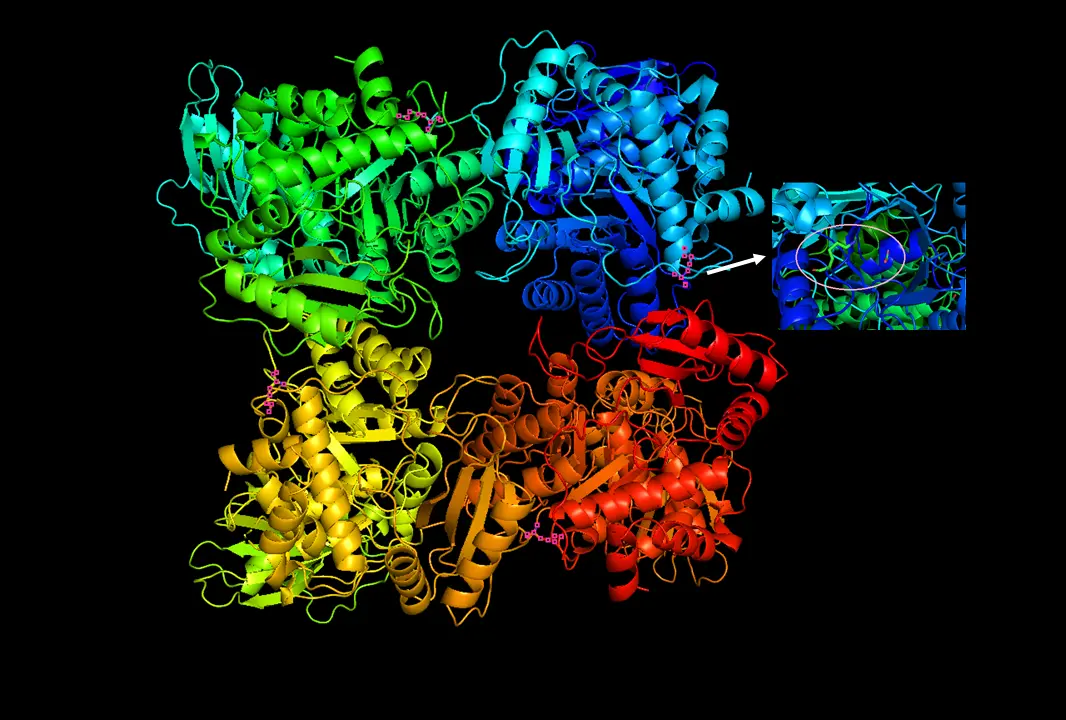

RuBisCO

A very old enzyme. Still fixing inorganic carbon in the biosphere through yet another mass extinction. Still grabbing the wrong molecule on occasion. Anyway, here are some more phosphoglycerates.

Kill your lawn, grow a garden. As you do this, look within and do the same.

- 27 Posts

- 504 Comments

3·2 个月前

3·2 个月前Agreed.

Also, I think it’s exacerbates, not exasperates.

2·2 个月前

2·2 个月前Ahhh, that makes sense. It sounds like a very interesting line of work.

Yeah, very curious how this happened.

3·2 个月前

3·2 个月前I see. Thank you!

Do you work with any energetics?

351·2 个月前

351·2 个月前Apparently not the first time.

Sucks that Ukraine might see fewer shells from this.

https://www.aesys.biz/products

Our portfolio includes a comprehensive range of energetics based on HMX, HNS, PETN, RDX, and TNT.

Energetics. Yeah that’s one way of putting it.

Not quite Oppau, but close.

51·2 个月前

51·2 个月前It doesn’t take in to account at all those who abstained.

Abstained? You mean helped Reagan win? How’d that strategy work out?

And it doesn’t list by generation just by 10-year increments.

False. Behold, arithmetic!

1980 election

Age (DOB) Range

18-21 (1962-1959) =3

22-29 (1958-1951) =7

30-44 (1950-1936) =14

45-59 (1935-1921) =14

60+ (1920-past)1984 election

Age (DOB) Range

18-24 (1966-1960) =6

25-29 (1959-1955) =4

30-49 (1954-1935) =19

50-64 (1934-1920) =14

65+ (1919-past)What they lack is a neat cutoff at 1945.

And generations don’t fall into neat 10-year increments.

No one is doing that.

Wikipedia:

The generation is often defined as people born from 1946 to 1964 during the mid-20th-century baby boom that followed the end of World War II.

More arithmetic! 1964-1946=18

At that point in time boomers were anywhere from 20 to 35.

1945-1960. Sure. Seems a breath away from a neat ten year increment, but sure.

101·2 个月前

101·2 个月前I disagree.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baby_boomers

In 1980, it was kinda close, 45v44 (18-21yo) and 44v44 (22-29yo), but I wouldn’t say they were “overwhelmingly against”. By 1984 they seemed quite in favor of him. They had help, no doubt, but they were not largely against; marginally against at most.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1980_United_States_presidential_election

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1984_United_States_presidential_election

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minsky_moment

According to the hypothesis, the rapid instability occurs because long periods of steady prosperity and investment gains encourage a diminished perception of overall market risk, which promotes the leveraged risk of investing borrowed money instead of cash. The debt-leveraged financing of speculative investments exposes investors to a potential cash flow crisis, which may begin with a short period of modestly declining asset prices. In the event of a decline, the cash generated by assets is no longer sufficient to pay off the debt used to acquire the assets. Losses on such speculative assets prompt lenders to call in their loans. This rapidly amplifies a small decline into a collapse of asset values, related to the degree of leverage in the market. Leveraged investors are also forced to sell less-speculative positions to cover their loans. In severe situations, no buyers bid at prices recently quoted, fearing further declines. This starts a major sell-off, leading to a sudden and precipitous collapse in market-clearing asset prices, a sharp drop in market liquidity, and a severe demand for cash.

The more general concept of a “Minsky cycle” consists of a repetitive chain of Minsky moments: a period of stability encourages risk taking, which leads to a period of instability when risks are realized as losses, which quickly exhausts participants into risk-averse trading (de-leveraging), restoring stability and setting up the next cycle. In this more general view, the Minsky cycle may apply to a wide range of human activities, beyond investment economics.

The term was coined by Paul McCulley of PIMCO in 1998, to describe the 1998 Russian financial crisis,[2] and was named after economist Hyman Minsky, who noted that bankers, traders, and other financiers periodically played the role of arsonists, setting the entire economy ablaze.[4] Minsky opposed the deregulation that characterized the 1980s.

Some, such as McCulley, have dated the start of the 2008 financial crisis to a Minsky moment, and called the following crisis a “reverse Minsky journey”; McCulley dates the moment to August 2007,[5] while others date the start to some months earlier or later, such as the June 2007 failure of two Bear Stearns funds.

2·2 个月前

2·2 个月前After several years of container ships being sunk on a regular basis, taken out by drone torpedoes of ever-increasing speed and power, the shipping industry had finally begun adapting to the new situation. It was adapt or die; there were only about eleven thousand container ships afloat, only two hundred of them in the Very Large class, and after forty of those were sunk the verdict was clear, the writing on the wall. They weren’t going to be able to stop the saboteurs, who still remained unidentified.

Maersk and MSC (a Swiss company) both began to rebuild their fleets, and all the big shipyards followed. It was that or die. That one of the biggest shipping companies on Earth was a Swiss company says something about the Swiss, and the world too.

An ordinary container ship was massive but simple. They were very seaworthy, being so big and stable that even when caught in cyclones and hurricanes they could ride them out, as long as their hulls kept their integrity and their engines kept running. And of course their capacity for cargo was immense. They were well-suited to their task.

So the first attempts at transitioning to ships the saboteurs wouldn’t sink involved altering the ones that already existed. Electric motors replaced diesel engines to spin the props, and these motors were powered by solar panels, mounted as giant roofs over the top of the cargo. This could work though the speed of the behemoths was much reduced, there being not enough room on them for the number of solar panels needed to power higher speeds. But if the supply chain of commodities was kept constant, in terms of arrivals at destination ports, these reductions in ship speed, and thus in economic efficiency, were just part of the new cost of doing business. “Just in time”—but which time?

Because they were slow. Fairly quickly there emerged specialized shipyards devoted to taking in container ships and cutting them up, each providing the raw material for five or ten or twenty smaller ships, all of which were propelled by clean power in ways that made them as fast as the diesel-burners had been, or even faster.

These changes included going back to sail. Turned out it was a really good clean tech. The current favored model for new ships looked somewhat like the big five-masted sailing ships that had briefly existed before steamships took over the seas. The new versions had sails made of photovoltaic fabrics that captured both wind and light, and the solar-generated electricity created by them transferred down the masts to motors that turned propellers. Clipper ships were back, in other words, and bigger and faster than ever.

Mary took a train to Lisbon and got on one of these new ships. The sails were not in the square-rigged style of the tall ships of yore, but rather schooner-rigged, each of the six masts supporting one big squarish sail that unfurled from out of its mast, with another triangular sail above that. There was also a set of jibs at the bow. The ship carrying Mary, the Cutting Snark, was 250 feet long, and when it got going fast enough and the ocean was calm, a set of hydrofoils deployed from its sides, and the ship then lifted up out of the water a bit, and hydrofoiled along at ever greater speed.

They sailed southwest far enough to catch the trades south of the horse latitudes, and in that age-old pattern came to the Americas by way of the Antilles and then up the great chain of islands to Florida. The passage took eight days.

The photo reminded me of this chapter of Ministry for the Future.

For some reason the video isn’t loading for me. Tried Voyager, Interstellar, and the catbox link in a browser, no luck.

I can hear shiny tuxedo noises just looking at them.

3·2 个月前

3·2 个月前Beans AND Trek?! Don’t work a linux distro into this meme format or the instance will collapse into a lemmy singularity–Bean3.

3·2 个月前

3·2 个月前They say naphtha is

an essential feedstock for the petrochemicals used in Taiwanʼs semiconductor and electronic component manufacturing

but where in the manufacturing process is it used?

A DDG search turned up a naphtha cracking plant in Taiwan that was converted in the construction of a new plant, and a bunch of hits for renewable naphtha methods, but no mention of how it’s used or why it’s needed.

I see. Thank you!